Water is one of the very few truly essential prerequisites for life. Our first concern as embryologists is the health and wellbeing of the next generation that we help bring into existence and the quality of water is essential to all our efforts in this regard.

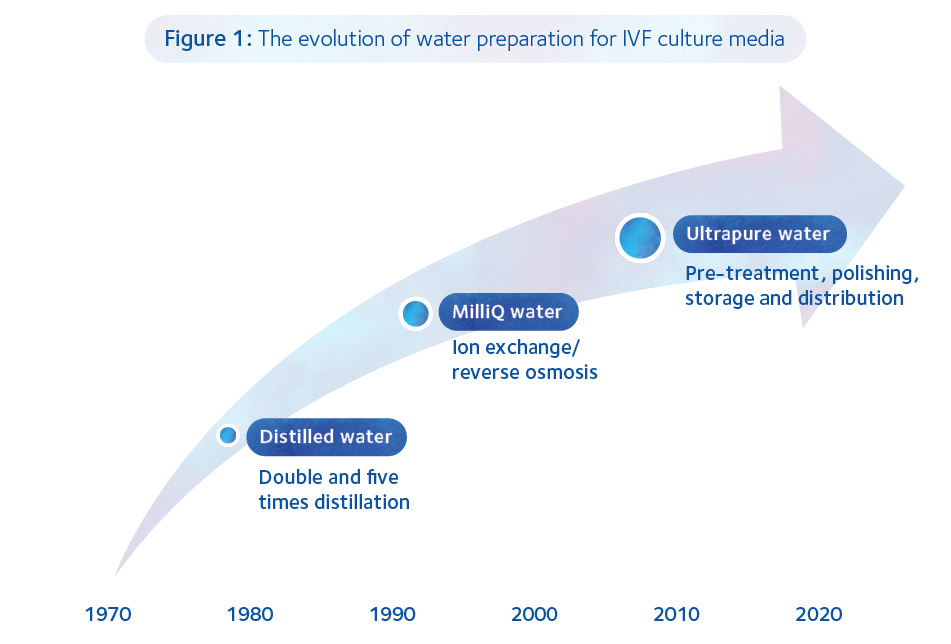

So, how has water quality evolved since the birth of the first IVF baby in 1978?

Coincident with the burgeoning clinical application of embryology in the 1980s, MilliQ ion-exchange/reverse osmosis water purification systems became standard in IVF laboratories. We would still subject the MilliQ water to five times distillation, discarding the first and last 10% of the distillate.

Our culture media QC included pH, osmolality, and MEA testing and proved good enough to supply to other IVF units, there being no commercially available culture media at that time, nor specific guidelines on sterility and quality testing prior to use.

The days before commercially available culture

In the days before clinical IVF, research embryologists were using two times glass distilled water for the preparation of mouse embryo culture media. However, for clinical embryology, it was assumed that five times distilled water might be better. So, at the Human Reproduction Unit of the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney, our response was to set up a still using five 5L round bottom flasks placed upon a gas-fired camp stove.

However, a catalyst was required to aid bubbling once the boiling point was reached, otherwise matters could become a bit explosive at the initiation of bubbling! So, a few small round glass balls were added to each flask, though there was some debate that metal ions might be leached from the glass balls during distillation. However, our paranoia didn’t end there since it was likely that tap water containing fluoride (as was the case in Sydney) might not be an ideal source of pure water.

Figure 2: Aquarium constructed using the original 5L flasks used for producing 5x distilled water

So, the Lab Director* took the initiative of taking home some large plastic bottles, similar to those placed upsides down in office water machines, and waited patiently for a storm when the roof and downpipes of his house would be washed clean by the deluge so that he could then attach the bottles and fill them with rainwater.

Happy days – five times distilled surface water; what could be better than that! Naturally, it passed our mouse embryo assay (MEA) at the time but, on retirement of the 5L flasks, they were set up as an aquarium with air bubbled through Pasteur pipettes and failed the fish survival assay (Figure 2).

Coincident with the burgeoning clinical application of embryology in the 1980s, MilliQ ion exchange/reverse osmosis water purification systems became standard in IVF laboratories. We would still subject the MilliQ water to five times distillation, discarding the first and last 10% of the distillate. Our culture media QC included pH, osmolality and MEA testing and proved good enough to supply to other IVF units, there being no commercially available culture media at that time, nor specific guidelines on sterility and quality testing prior to use.

The application of good manufacturing practice to culture media production

The end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s witnessed the demise of IVF lab-produced media as various companies concentrated upon producing commercially available culture media of high quality and consistency. Nevertheless, water quality has remained central to the evolution of both single-step and sequential culture media.

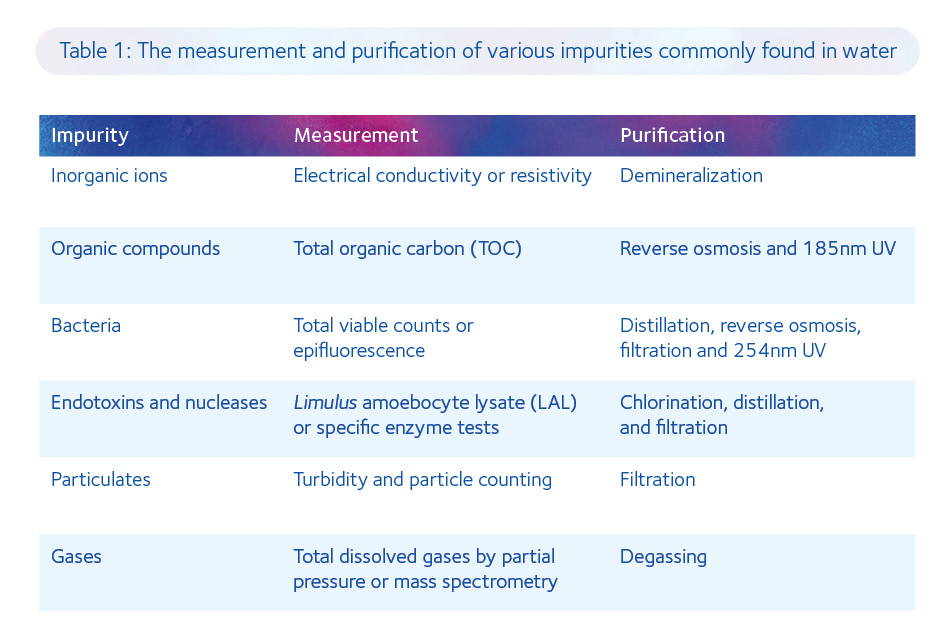

Nowadays, the basic principles behind the production of MilliQ water still apply but the processes have become increasingly sophisticated and the testing more exacting. Indeed, there is a specific treatment for each contaminant commonly found in various sources of water (Table 1).

The production of ultrapure water of the highest specification for culture media manufacture is now a four-step process: pre-treatment, polishing, storage, and distribution. Pre-treatment of municipal water includes removal of chlorine using sodium metabisulfite, removal of large particles by filtration (5µm), removal of microbes with UV irradiation (254nm), removal of divalent cations (eg. Mg2+ and Ca2+) using parallel ‘softeners’, and removal of ions (approximately 96% of salts in solution), other microorganisms and smaller particulates by reverse osmosis.

Polishing of pre-treated water includes the exchange of charged species for H+ and OH– ions using a mixed bed of cationic and anionic resins within deionization tanks, elimination of any microbes that may have accumulated within the deionization tanks using UV irradiation (254nm), and removal of any dead bacteria and viruses by ultrafiltration (0.03µm).

Storage and distribution are effectively a second polishing step, with the prevention of biofilm growth by continuous water circulation, removal of any residual bacteria and endotoxins using ultrafiltration (with a molecular weight cut-off of 6000Da), and elimination of any organic carbon that may have developed during distribution by UV irradiation (185nm). It is evident that we have come a long way since the dawn of the golden age of IVF and that the quality of water used for manufacturing culture media is now approaching its zenith.

*Acknowledgement: I would like to thank the Lab Director mentioned in this blog, Dr Ian Pike, for providing some of the ‘inside’ information regarding water purification in the 1980s and Figure 2.

Steven Fleming PhD is an Honorary Associate at the University of Sydney and Director of Embryology for ORIGIO. Previously, he was the founding Scientific Director of Assisted Conception Australia, and a Senior Fellow at the University of Queensland.

Steven Fleming PhD is an Honorary Associate at the University of Sydney and Director of Embryology for ORIGIO. Previously, he was the founding Scientific Director of Assisted Conception Australia, and a Senior Fellow at the University of Queensland.

After completing his doctorate in 1987, he undertook postdoctoral research at the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney, and from 1993-1997 he was appointed Lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Nottingham in England, where he established the world’s first Master’s degree in Assisted Reproduction Technology with Simon Fishel PhD.

From 1998-2008 Steven was the Scientific Director of Westmead Fertility Centre in Sydney and appointed Senior Lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Sydney. He is the recipient of numerous research grants, and an author and editor of several books, book chapters and peer reviewed journal articles. Steven’s research interests include cryopreservation, endometrial physiology, endometriosis and oocyte maturation, among others.

My Clinic is in the United States

My Clinic is in the United States My Clinic is in Canada

My Clinic is in Canada